Gegenüber konventionellem 3D-Druck mit Harzen und Licht, das 3D-Objekte quasi zweidimensional mit Schichtbildern aufbaut, kommt beim neuen Verfahren eine Dimension hinzu. Es kann also 3D-Objekte dreidimensional, direkt auf einmal herstellen.

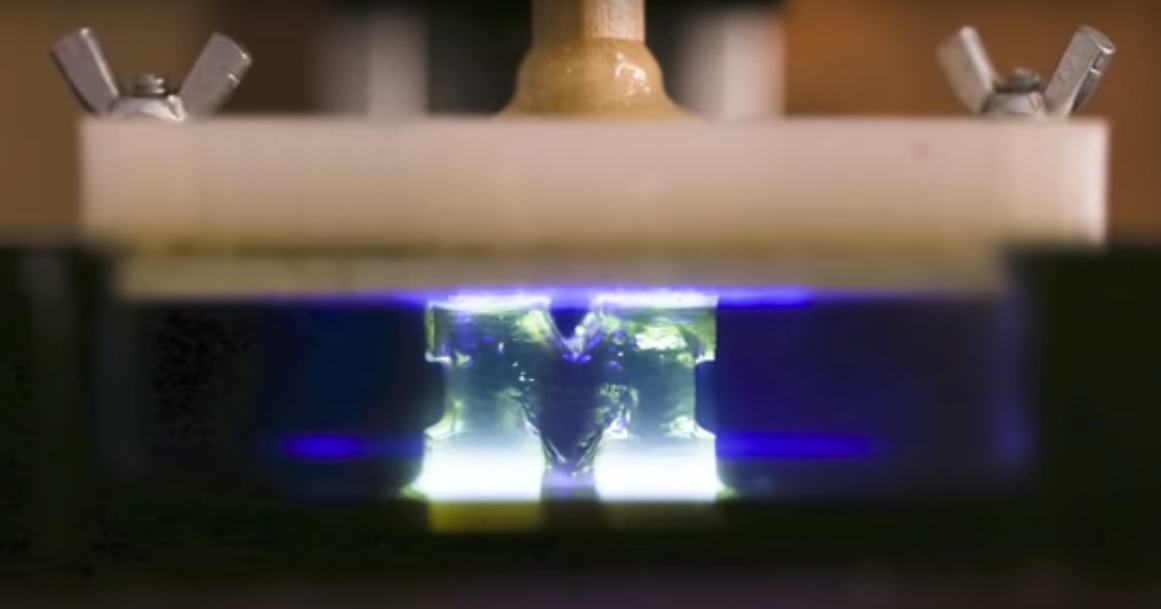

Das neue Verfahren verfestigt das flüssige Harz mit Hilfe zweier Lichtquellen und kann daher präzise steuern, an welchem Raumpunkt das Harz aushärtet und wo es flüssig bleibt. Eine Lichtquelle besorgt die Verfestigung des Harzes und die andere stoppt diesen Prozess. Da hier dreidimensionale Blöcke auf einmal belichtet werden können, ist diese Technik nicht nur extrem schnell, sondern auch der erste „echte“ 3D-Druck überhaupt.

Durch die Schaffung eines relativ großen Bereichs, in dem keine Verfestigung auftritt, können auch viskosere Harze, potenziell mit verstärkenden Pulveradditiven, zur Herstellung stabilerer Objekte verwendet werden. Das Verfahren übertrifft auch die strukturelle Integrität des Filament-3D-Drucks deutlich, da dessen Objekte Schwachstellen an den Schnittstellen zwischen den Schichten aufweisen. Eine frühere Lösung für das Problem der ungewollten Verfestigung war ein sauerstoffdurchlässiges Fenster. Der Sauerstoff dringt dabei in das Harz ein und stoppt die Verfestigung in der Nähe des Fensters, so dass dort ein Flüssigkeitsfilm entsteht, der es ermöglicht, die frisch gedruckte Oberfläche wegzuziehen. Da dieser Film aber nur etwa so dick wie Tesa ist, muss das Harz sehr flüssig sein, um schnell genug in den winzigen Spalt zwischen dem neuen, erstarrten Objekt und der Oberfläche zu fließen, wenn das Objekt weggezogen wird. Dies beschränkt diese Art des 3D-Drucks auf Harzbasis auf kleine, kundenspezifische Produkteserien oder Einzelanfertigungen, wie z. B. Schuheinlagen etc.

Die neue Technik: Weil statt Sauerstoff eine zweite Lichtquelle zum Stoppen der Verfestigung genutzt wird, konnten die Forscher sehr viel größere Lücken und somit millimeterstarke Schichten erreichen, in die das Harz einige Größenordnungen schneller fließen kann. Das Ganze funktioniert natürlich nur mit speziellen Harzen, denn in herkömmlichen Systemen gibt es nur eine Reaktion. Ein Photoaktivator härtet das Harz überall dort aus, wo Licht ist. Das in Michigan verwendete Harz hat hingegen auch einen Photoinhibitor, der auf eine andere Lichtwellenlänge reagiert.

Anstatt nun wie bei konventionellen Verfahren die Erstarrung in einer 2D-Ebene zu steuern, erlaubt die Lösung aus Michigan mit zwei Lichtfarben das Harz im Prinzip jeder beliebigen 3D-Position in der Nähe des Belichtungsfensters zu härten und somit dickere 3D-Schichten auf einmal zu drucken, was die Geschwindigkeit enorm erhöht.

Compared to conventional 3D printing with resins and light, which creates 3D objects two-dimensionally with layered images, the new process adds a dimension. It can therefore produce 3D objects three-dimensionally, directly at once.

The new process solidifies the liquid resin using two light sources and can therefore precisely control where the resin cures and where it remains liquid. One light source solidifies the resin and the other stops this process. Since three-dimensional blocks can be exposed here at once, this technique is not only extremely fast, but also the first „real“ 3D printing ever.

By creating a relatively large area where no solidification occurs, more viscous resins, potentially with reinforcing powder additives, can also be used to produce more stable objects. The process also significantly surpasses the structural integrity of filament 3D printing as its objects have weak points at the interfaces between layers. An earlier solution to the problem of unwanted solidification was an oxygen permeable window. The oxygen penetrates into the resin and stops solidification near the window, creating a liquid film that allows the freshly printed surface to be pulled away. However, since this film is only about as thick as tape, the resin must be very liquid to flow quickly enough into the tiny gap between the new solidified object and the surface when the object is pulled away. This limits this type of resin-based 3D printing to small, customer-specific product series or custom-made products, such as shoe inlays, etc.

The new technology: Because a second light source is used instead of oxygen to stop solidification, the researchers were able to achieve much larger gaps and thus millimeter-thick layers into which the resin can flow several orders of magnitude faster. Of course, the whole thing only works with special resins, because in conventional systems there is only one reaction. A photoactivator cures the resin wherever there is light. The resin used in Michigan also has a photoinhibitor that reacts to a different wavelength of light.

Instead of controlling solidification in a 2D plane, as with conventional methods, the Michigan solution with two light colors allows the resin to cure in principle at any 3D position near the exposure window and thus print thicker 3D layers at once, which increases the speed enormously.